First Person

The Cost of a Needle

Why would a knitter—a lover of wool, slowness, and the gentle defiance of making things by hand—find herself drawn to a museum full of metal needles, mismatched displays, and the lingering scent of industrial soot? It wasn’t an obvious pilgrimage.

I came expecting a quaint dose of local history, maybe a few charming artifacts behind glass. I stayed for the Victorian needle-polishing machine that looked like it belonged in a dungeon rather than a factory, equal parts engineering marvel and medieval torture device.

Forge Mill Needle Museum sits just outside Redditch, nestled beside a murmuring stream that once powered the water wheels inside. At first glance, it looks like the kind of place schoolchildren get dragged to on wet Tuesdays: low red brick, a small gift shop, and that particular English damp that clings to your ankles no matter the season.

The signage is honest rather than slick, and there’s a quiet determination to the whole place, as though it knows it’s slightly odd, slightly forgotten, but refuses to go anywhere.

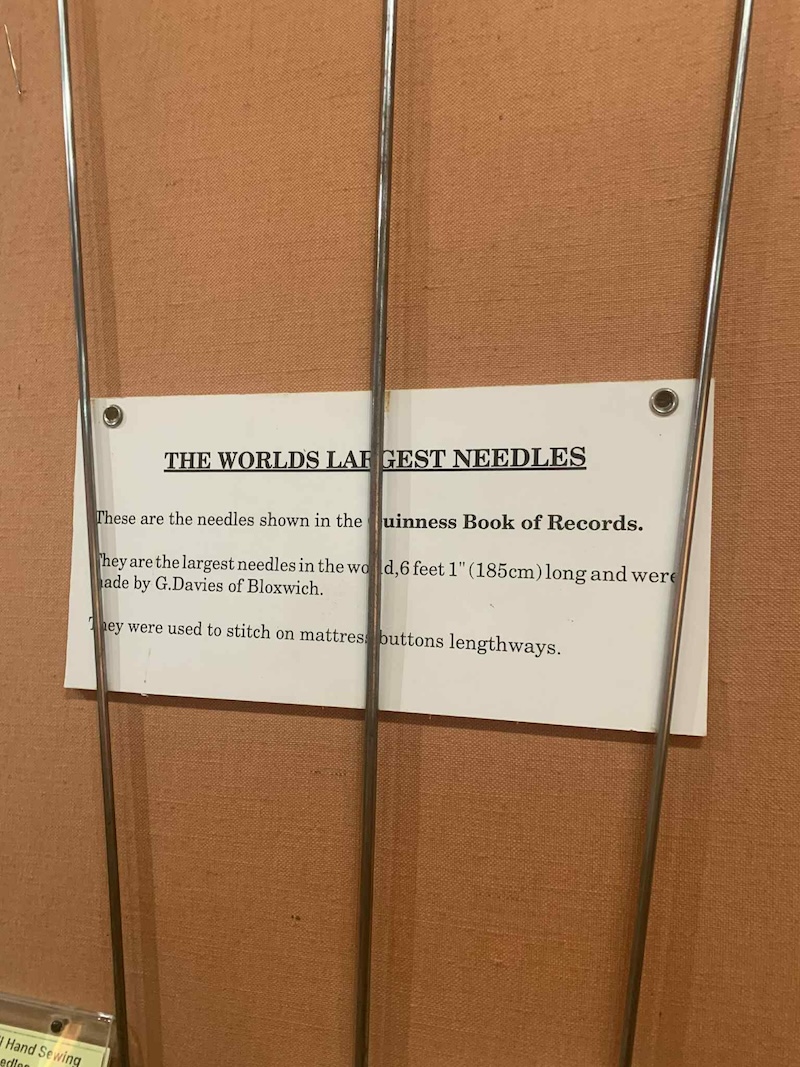

At its peak, Redditch produced around 90% of the world’s needles. Not just sewing needles, but surgical, darning, milliner’s, mattress, beading, and fishhook variants—some no thicker than a strand of hair, others fat and blunt and built to puncture leather.

I expected a quiet afternoon among curious oddities like wooden spools, old advertisements, perhaps the occasional Victorian sampler. What I didn’t expect was how violent needle-making once was. Every step of the process seemed designed to shred lungs, blacken hands, or crush a limb or two, especially if you were poor, small, and considered expendable.

The machines were loud and unforgiving; the metal brittle before it was tempered. Needles began as wire, sliced, sharpened, stamped, polished, and boxed, each step requiring its own mini-factory line, often manned by children or underpaid women in dim, freezing outbuildings.

The sharpening (known as “pointing”) was one of the worst jobs. The men who did it were only allowed to work for a couple of hours at a time before being sent outside to recover. And by “recover,” I mean “cough.” Violently. They’d expel neat little globes of metal filings mixed with lung lining, proof that the body was physically giving up pieces of itself just to earn a wage. They called it “Grinder’s Rot.”

And they did it again the next day. Most pointers did not live beyond the age of 30.

One display described how workers would spend hours polishing needles in rotating drums filled with oil, grease, and powdered stone. The dust this produced coated the air—and, eventually, their lungs—with something close to concrete.

Health officials tried introducing protective masks featuring magnets designed to pull the metal dust away from the mouth, but many refused them. “Less danger means less money,” one worker had explained. If a job became safer, it also became less skilled. If it became less skilled, it paid even worse than the pittance they were already earning.

That was the moment I realized this wasn’t really a museum about needles. It was a museum about labor, risk, and the cost of speed, which was paid, always, by someone else.

After leaving the museum, I found myself handling my own knitting needles as if I were holding something heavier, sharper, and somehow more alive than before. The smooth wood and gleaming metal suddenly carried the weight of those unseen hands and lungs, of countless hours bent over machines and workbenches in cold factories.

The needle was no longer just a tool for making pretty things; it was a vessel of history, endurance, and quiet sacrifice. I could feel the trajectory of the needle’s journey—from wire and stone dust to something warm and personal—threaded through my fingers with every loop of yarn.

Visiting Forge Mill made me think about how knitting—and craft more broadly—exists as a strange tension between histories of exploitation and acts of resistance. The needles were once mass produced, churned out in factories where speed was king and human life was often the cheapest cost. Yet today, the very same needles have become tools of quiet rebellion against that logic, instruments of slowness, patience, and intentionality.

As I stepped away from Forge Mill, the sound of water slipping over the old sluice gates echoed in my ears, steady and relentless. In my palm, I turned a single needle over and over, its cold metal now warm from my skin, a tiny weight carrying centuries of hands, some calloused, some delicate, all worn from work and hope.

Now, every time I slip that needle through fabric, I remember the clatter of the forge and the girls who packed needles by hand for twelve hours a day, six days a week.

It’s funny, isn’t it? I spend my days championing slow making, yet half my time is swallowed by refreshing social feeds, hunting the next crafty trend. Maybe slow resistance is a work in progress, like a knitting project where the pattern keeps changing.

Love this article? We love bringing it to you! MDK’s free daily content is made possible by your purchases from the MDK Shop. Take a look around. Browse our Sale page here. Thank you!

Fascinating story. Thanks for taking the time to write it.

Can someone tell me why I have watery eyes and a lump in my throat after reading this? Absolutely so humbling.

That was so heartbreaking… and an eye opener… and a vessel for added gratefulness. Tools that I use every day have taken their toll on others before me; I am grateful for their hard work and their sacrifice; even though the process is much more automated, how many people still come in contact with the chemicals used to make our modern needles? It behoves me to take care of my tools so that they don’t need replacing – having just broken two 2.5mm bamboo needles this past week. I will not throw them away. No. I will file both ends carefully so that they can be re-used. Thank you Ashleigh-ellan for your thoughtful article and beautiful photographs.

I found a video from 2012 (although it sounds & looks older) regarding sewing needle making practices; they don’t mention where they are being manufactured, and they don’t mention whether the process is unhealthy, and whether workers in these factories wear protective gear https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wZJPpuL2sqQ

I agree with you completely.

And thanks for the video…amazing! Makes me wonder how the machines that do all this work were thought up.

The article was most interesting, particularly the bit about forgoing safety in fear of reduced income. Knowing the tragic events behind the industry, I shall have more respect for my humble needles.

Such an interesting video! Thanks. Good share.

The MDK post made me a little softened in the heart too. Life has been so hard for laborers. We have been fortunate to reap the benefits of unions and enlightened politicians — let’s keep those intact to keep ALL people safe and thriving!

The packaging on the needles says they are from Prym, a North American needle maker affiliated with Dritz and Omnigrid. Their knitting needles are great! Thanks for this fascinating video.

Prym is actually a German company dating back to 1530. There’s a good article about them on Wikipedia.

I, too, thank Ashleigh-ellan for this post, and IPY for the video.

Thanks for including the video link, fascinating!

Thank you. The previous 3 writers have said it all. This is humbling–we take so much for granted.

In a few powerful, beautifully written paragraphs you have given me a important awareness. What, a few hours ago, were simple tools that I took for granted on a daily basis now hold new respect and a profound debt to those who sacrificed so much to make them. I will read this article to my grandchildren who watch me knit and hem and mend. We can’t forget.

Usually I am a lover of social history, but this little corner of it just horrified me. Slow making nothing. This was slow death. Along with coal mining and similar insidious means of human exploitation. In college I was fascinated by a book describing everyday Roman civilization which included a description of their eating utensils. Now I will think twice every time I pick up a metal size 8 circular or a tapestry needle – or a fork for that matter.

Yes, there is a fascinating book about eating utensil history, titled Consider The Fork.

Thank you for this. Such a thoughtful and thought-provoking piece. I loved it! I take so much for granted in this life. This was a good reminder for me to be more thoughtful about how I am able to pursue this hobby that I love so much.

Factory work was dangerous. Even into the 20th c and to the present Cotton mills, meat processing plants …(Sinclair’s The Jungle anyone? Elizabeth Gaskell’s novels of Manchester? Watches with radium dials?)

I once watched a (modern) blacksmith make a nail – quite a time consuming process.

Interesting museum!

The past isn’t all pretty.

I have a collection of old needles, I’ll appreciate them even more now, thanx

Through tears I send you thanks for this excellent article. It is a good thing to give pause and recognize the history of the price paid by those before us and, again, give thanks for those who fought (and fight) to fuel the labor movement.

Thank you! This was a very interesting essay. I had never thought about how the early needles were made.

Things you don’t think about as you knit. Very interesting. Enjoyed the tour of a needle museum, I have been knitting for 76 years and never knew.

Sinserly Birgit

Beautifully written article. I will never understand how a person could mistreat/exploit another human. And yet it continues . . .

Terrific article!

And how I wish the Needle Museum had been in existence when I worked on the archaeological excavations at the adjacent Bordesley Abbey in 1977. After learning about the local industry, I hunted down a packet of Redditch needles.

I’m so sad Years and years ago we wre in the UK and I mentioned to our landlady that I wanted to visit the needle museum and she said No you don’t,it’s very boring.so we never went and now I never will. Too far and too old.

Thank you for this wonderful piece. So important!

Wow! It takes your breath away. Thank you.

Thank you for an interesting article. We can all be thankful for safety provisions that continue to come into place to protect workers of all kinds.

Fascinating. I never stopped to think about how they were made.

i really loved your article today- thank you!

Since childhood I was interested in how certain things were made, often asking my Mum to explain this or that. The metal things? I always assumed that some machine was used for that. Still, before there were machines, say in the antiquity or slightly later, how were they made? Of course I was assuming that come 19th century the machines for needle production were already in existence. Alas! What an eye opener this article is… and as always, how enlightening visits to the museums can be!

Thank you Ashleigh-ellan for this!

Beautiful writing! Thank you for sharing this. Moving to think about those workers who were taken for granted by so many who used the items they produced!

Actually, gut wrenching article! The exploitation of workers to the benefit of the rich and powerful. And, unfortunately, continues to this day in many different forms. Man’s inhumanity to man.

Thank you for an eye opening article.

A very thoughtful look at a piece of history I had never even considered! Exploitation and resistance are such powerful forces in a society right at the point of a needle. Look forward to more of your writings. Thank you!!!

Thank you — what a beautiful essay. Like the other commenters, it’s an aspect of crafting I had never even thought about.

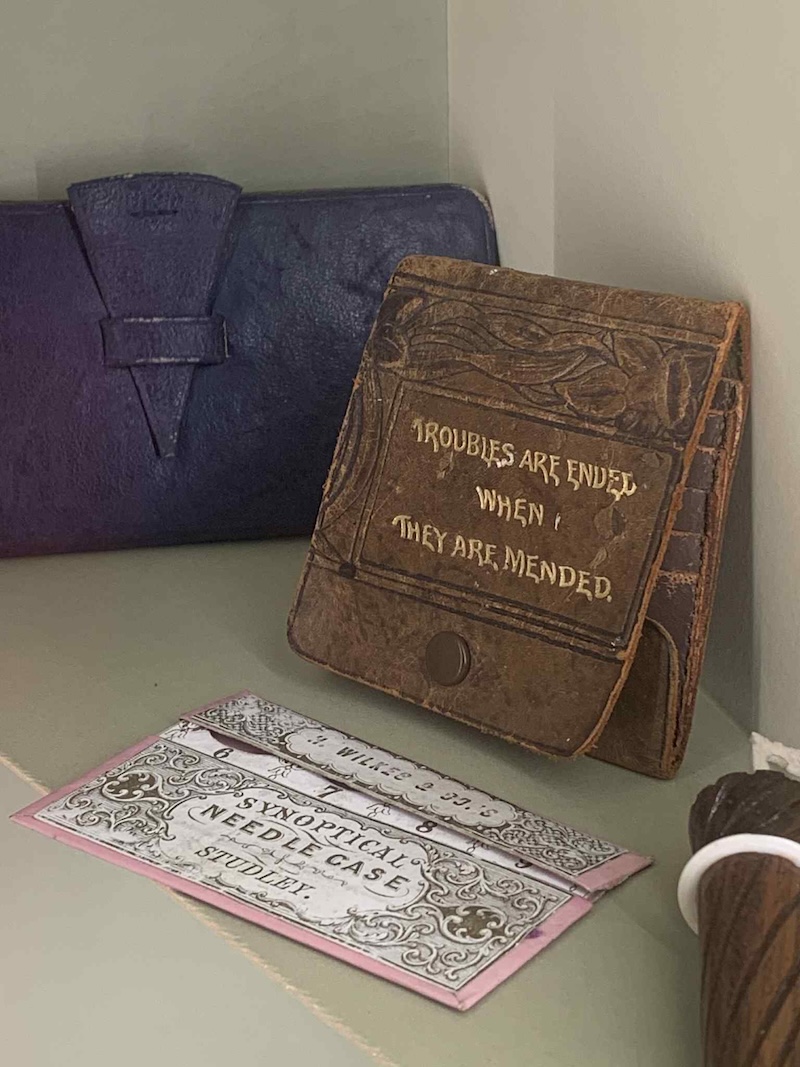

My mother and most of our female neighbours worked at the Needle Industry factory in Studley. There were also a great many women that were home workers. During the 1950’s girls leaving school were all offered work at Needle Industries.

The girls were very skilled and fast at sorting needles as it was all peace work ( the more you worked the higher your pay).

My mother worked in the metal testing laboratory .

Thank you for a very eye-opening post this morning.

Wow. An abrupt humbling to those gone. Thank you for the tour.

Wow. Interesting story.

One of the very best! Thank you very much.

What a fascinating article!!! Thank you for writing it. The horror of that coughing!

What a fabulous article. Thank you for writing about the needle industry in Redditch. Several of my female ancestors living in Redditch and Beoley were “needle straighteners” according to census records.

My 4x Great Grandfather, Henry Millington, was the clerk at Washford Needle Mill, Ipsley, Redditch. Henry was also involved in the Chartist movement with a nomination for General Council Chartist of Great Britain in 1841. I’d like to think that he helped to improve working conditions.

This leaves me wondering if any of my ancestors were actually at Forge Mill.

Thanks again for a wonderfully poignant article.

Thank you for this very interesting and well-researched article. I must “demand” now a full accounting of the one-sided Tom Daley beef.

Beautifully written. Thank you. Very interesting.

What a moving experience. Thanks for sharing this significant piece of history.

Omg great article – would definitely visit this museum- reminds me of a tour of lower east side tenement museum in NYC- about garment workers . I am a knitter and sewer and will like Ashley look at my needles differently!

Fascinating. Thank you! I wonder if knife-making was similar?

I had no idea the history of this product. How sad to think people of labor are expendable (even today). Today, many countries have safety laws but there are autocratic countries who treat people as disposable.

What a gut-wrenching article. I will never look at a needle in the same way. A fascinating bit of history, but like so many tools we tale for granted, who knew the human toll it took. Articles like these makes us appreciate what industrialization has done to help.

Wonderful, sad, empowering all at the same time. THIS is why we have workplace protections today, built on the failing (and dying) bodies of our ancestors. THIS is why there is rebellion against those who would remove the safeguards for the sake of money. Thank you.

Hear, hear!

Thank you for this article. Despite growing up in the area I’ve never visited Forge Mill. It’s about 10 minutes drive from my Mom’s house and I will visit next time I cross the Atlantic for a visit.

“Maybe slow resistance is a work in progress, like a knitting project where the pattern keeps changing.”

Thank you for this – I’m going to carry that notion with me.

Everything is a social statement and the history of a country.

Thank you for writing such a vivid account. Time often robs us of a perspective about others labor.

The writing in this article is beyond superb. Thought provoking, haunting, beautiful.

Such a profoundly revealing piece. I thought I knew a lot about needle production but I was supremely ignorant of the human cost of its industrial history. Thank you for writing this. It has illuminated my thoughts and feelings about my passion for textile handiwork.

Thanks

A very appropriate article as we approach Labor Day.

Solidarity–the union makes us strong.

Thank you for a very informative article. I had no idea that needles were made that way in the beginning and how people endured and not endured that life. I had to look up how needles were made today and, of course, less hazardous and mostly machine automation. But still one takes for granted such a thin small needle!

Thank you for this piece. I had never thought about needle production before. The poor had/have such hard lives