Beyond Knitting

Spells in the Stitches

There has always been a little witchcraft in knitting.

How else do you explain the way yarn multiplies in the stash as if by moonlight, or the ancient curse that says gifting a boyfriend sweater is the surest path to heartbreak?

Even the most practical among us will admit that second sock syndrome feels less like poor motivation and more like a hex. We laugh, we frog, we swatch like we are warding off misfortune, but the truth is this: every knitter already lives inside a world of spells.

Our tools may not be wands, yet the needles click and conjure all the same.

According to Cecil Williamson, “West country (U.K.) witches retain a strong Celtic tradition in much of their spell making incantations, such as repeating a thing over and over and over again. So using witches’ knitting needles (which must be blunt, thick and made of glass), they repeat the spell stitch by stitch. When the spell is regarded as being real strong the knitting is taken off the needles and burnt.”

But before needles clack or spindles whir, we sense the power in fabric. Textiles warm us, they conceal us, they declare who we are. They can even change us.

Elizabeth Lee’s essay A Spell on the Industry suggests something striking. As women became more visible in the textile economy, they also became more visible in the courts of witchcraft. Between 1580 and 1650 accusations soared at the same time that women crowded into weaving rooms and dye houses. By 1604, more than half of all weavers were women. In Florence, eight out of ten women who listed an occupation worked in textiles. And that connection between women and transformation made neighbors uneasy.

Textiles also stirred anxiety because they were not only useful. They were transformative. For the first time, ordinary people could buy more than bare utility. Fashion emerged as a restless, unsettling force.

The very word “fashion” began to mean counterfeit or pervert. If a farmer’s wife wore silk, how could one tell who belonged where? Clothing was dragged into the same atmosphere of suspicion. It could lift you into new status or mark you as dangerous.

The theater made this power obvious. Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth was never called a witch, yet her promise to dash the brains of her child and her role in regicide echoed the same fears.

A woman who twisted the roles of wife and mother became unnatural. A woman who bent the rules of authority threatened the very body politic. Audiences understood. They were already seeing their neighbors accused for less.

Authorities worried too. King James himself saw witchcraft as treason, a direct refusal of his earthly authority. If a woman could subvert her husband at home, what was to stop her from unraveling the monarchy?

This fear of domestic rebellion was one of the reasons the household became such a contested space. Women were meant to keep the hearth and produce children. When infants died, midwives were accused of witchcraft. When crops failed, the spinner or seamstress was accused of malice. Even everyday household roles could become evidence of unnatural feminine behavior.

The danger was not only that women worked. It was that they worked with objects tied so closely to identity. Cloth lived against the skin. It carried memory. The idea that clothing held secrets was not metaphorical. In New England, dresses were admitted into evidence. In Renaissance London, sumptuary laws tried to stop people from dressing “above their station.” But enforcement was patchy.

Of course, not every witchcraft case was about gender. Men were accused, too. But as Christina Larner wrote, witchcraft was not a gendered crime, it was gender specific. Suspicion clung to women. It clung because women shaped the very stuff of identity.

And here lies the feminist resonance. To demonize a woman for spinning or sewing was to strip her of authority over creation itself. Whoever holds the thread decides what will hold and what will unravel. That was too much power to ignore.

Yet society could not function without this labour. By 1700, women no longer seemed so threatening, not because they worked less, but because their work was too essential to deny. The witch hunts dwindled as industrial organization grew, but the memory lingered. It still lingers. Every time we speak of “women’s work,” we hear the faint echo of the accusations that once turned needles and distaffs into tools of suspicion.

The story does not end in the seventeenth century.

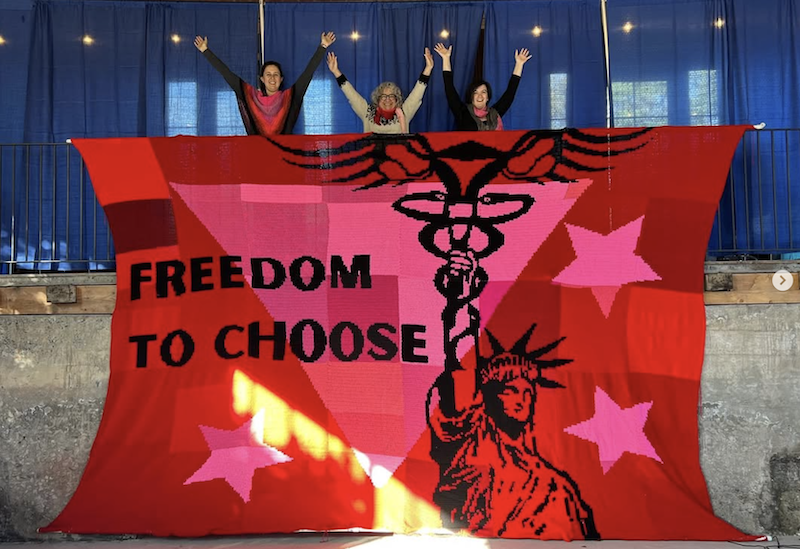

The Liberty Crochet Mural at A Woolen Affair in October 2025.

Today, the witch has been reclaimed. Feminism embraces her as a figure of rebellion. On social media she is everywhere, altar beside embroidery hoop, spell stitched into protest banners, quilts spread out as memorial.

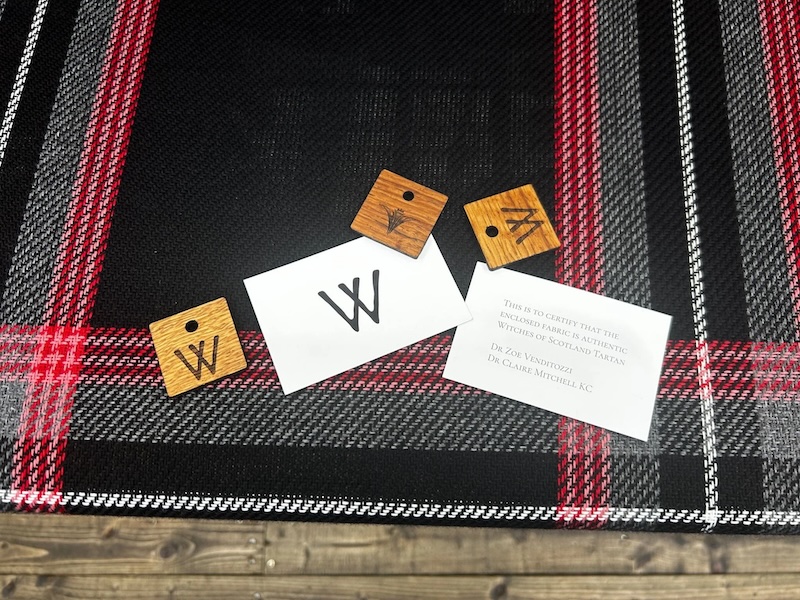

In Scotland, a tartan has been designed to honor the women executed as witches, every thread count and color chosen to remember blood and ash. Textile magic never really went away. It simply waited for us to see it again.

And of course, knitting has its own quiet spells. To knit is to bind and release. It is to risk unravelling and to make pattern from chaos. It is, in its way, enchantment.

Which is why I think every knitter should go ahead and embrace their inner witch. You already practice a little sorcery every time you pick up the needles. You conjure warmth, beauty, identity. You bring something out of nothing but a strand of string. That is power worth claiming.

So next time you cast on, consider it an incantation. And if anyone asks why you are grinning like a witch at your work, tell them the truth. You are one.

Really enjoyed this article.

Really enjoyed this article. Did not know about the tartan. May need to get it

There’s a podcast called Haptic and Hue, which has an episode dedicated to the tartan.

I love this article!

This was a very interesting read. I appreciate the thought you put into it and your perspective. I am an artist who mostly does weaving on frame looms. As a woman of faith, I see my identity as a creation who was created to create. My art is an act of worship to God. As I create, I pray over what I am working on and allow to Holy Spirit to move through my imagination for what I make. It’s been a very healing process for myself as well as others and how I approach my art from this mindset. I wanted to offer another perspective on creating.

So pleased to read your comment as a fellow woman of faith who runs a natter and stitch group which is 30 strong and is ran in my church. It is also sponsored by the church which makes it free for anyone to attend and it is loved by everyone. We have a number of Christian’s in the group who I’m sure, like me would be mortified at the link to witchcraft. I’m grateful for the idea of praying as we knit or crochet each row of stitches in order to create something beautiful with the gifts we have been given by our creator. Keeping our hands and minds busy means that we also prevent the devil from making work from idle hands. God Bless xx

I think the same way. When I am making blankets, my subconscious mind is praying to keep them warm and feel well when they pull it over onto them. Used as a shield from the cold and the evil. I did enjoy reading the history and view of the writer

Beautiful perspective Erika. Thank you for your perspective.

Thank you for this article–it’s thought-provoking and empowering. I needed this today.

How interesting! Thank you so much. I find myself wondering if the very fact of women in groups doing almost anything together didn’t pose a measure of threat to men in charge. As in, modern men wonder why we go to the ladies’ room in pairs. It only takes 2 of us to make them wonder what we’re up to!

This is what I saw Anne–a “Damned if you do, Damned if you don’t” approach to women’s work. That view changed when men did it. Think of Chefs and Designers. (thank heavens we’re in a time where this is shifting, but still…)

But I do have the answer for WHY women go to washrooms in pairs…the long lines make it essential to bring your own entertainment!

Love this! thank you

Fascinating article. Thanks!

Loved this fascinating article! How about another about that tartan?

Good article. Food for thought especially in today’s politics .

Absolutely love this! Thank you Ashleigh ❤️

Your article was great. I have come across spells cast while spinning, but knitting? That could b a lot of fun!

And I would b proud to wear that tartan of the murdered women.

Ever read “Women’s Work: the First 20,000 Years?” And do you have a bibliography?

I dont know about the other references in the article or.the comments, but here’s a link to the info about the tartan and the related campaign, Witches of Scotland: https://www.witchesofscotland.com/ and here’s the episode of Haptic and Hue: https://open.spotify.com/episode/7Iqw7bgIOt4CceoHyl739d?si=5t2_8-aOSGewzCInjQlKLw

That’s one of my favorite books! I was lucky enough to have the author as a professor in college – she set me on my path in so many ways.

Love this! Thank you!

What an interesting and well written piece! I agree that there is magic in knitting, in many ways!

OMG! I love this so much!!! Love this history and the telling!!! Whoever holds the thread…

Fascinating look at a connection that remains largely unseen and unacknowledged. Thanks for bringing this to light.

Rumination while knitting. Yes, that describes why we sometimes turn to our needles. That often leads to calmness and even joy. There has to be magic in that. Thanks for sharing this with us.

Love this, Ashleigh. Thank you.

Thanks for the article. I loved the Freedom crochet at Woolen Affair! So Powerful.

We do create magic! We create life as well as objects to gift and wear. We (women) are the makers of our world…..

Ashleigh-Ellen, this is amazing. Thank you!

Excellent article! Thank you!

Great article ! Thank you.

Great article and I am very curious about the tartan!

Thank you for this super interesting article! The correlation is striking. What a conversation starter… some more bibliographical info would be useful as well… What a material for a longer dissertation and more, but let’s start with: “ Whoever holds the thread decides what will hold and what will unravel.” This along with the image at the beginning made me think about Greek mythology and in particular the 3 Moiras… One who was spinning the thread (of life) the second who was measuring or winding it and the third who was cutting this thread (here she is breaking the thread with her teeth). Here you go with the three women and a thread of life!

On another note it is really a pity that these days young people aren’t taught much about antiquity, its myths were full of everyday life as it was observed… then woven (no pun intended) into the stories (virtual soap operas) about the Greek deities, reflecting our human weaknesses or heroism. Eventually we find the story of Penelope or Ariadne both linked to threads, cloth, weaving, etc…

I agree that ancient myths have a lot to teach our children. My son, in a traditional school, did not learn much about Greek and Roman myths, but my daughter, in a non-traditional school, was able to take a mythology course that also covered Japanese, Australian, and African myths. I think they provide a deeper cultural understanding than just battle dates.

Love this. Look forward to reading more articles by Ms. Kavanagh!

Great article! I just returned from a tour of Scotland and Shetland wool week. We (a lot of knitters) had the pleasure of touring the Prickly Thistle’s manufacturing site and see them weaving several tartans and the witches tartan as well. It’s beautiful and lovely to see in person. They make kilts obviously and other beautiful items of clothing for women. The founder Claire gave us a great and inspiring tour. One of the high points of our Scotland tour. I would highly recommend clicking the link in the article and checking them out!

As a knitter and a witch, I loved this!

I encourage everyone to listen to the Witches of Scotland podcast. So many women (and some men) put to death by the state. So many women lost. So many women.

Excellent

Loved the read

Interesting insights. You probably know that women who made beer (ale wives), also became suspect, not because they made alcohol, but because the craft of beer making gave them economic independence. Their hats, which were tall and pointed to make them visible in the markets, became what we now use as a symbol of the witch.

Fascinating about the alewives hats!

What a beautiful essay! I have knitted since I was ten yearss young. I will manifest my wishes with every row. Thank you for this!

Beautiful Tartan!

I live this. I am a knitter, but actually. I know onto things I make for people. Spells for health, happiness, prosperity, love.

Baby blankets are my favorite!

LOVED this. It brought tears to my eyes. Thank you so much! (Like many others in the comments, I was particularly excited to learn about the tartan…)

Now the quest–find the best pattern for a sweater to wear with the Witches of Scotland tartan kilt. Make that sweaters, plural. One for evening, one for hiking, one for lollygagging around town.

Loved this. Maybe such an incantation will help me focus

Brava!

Absolutely enthralling and so true. Thank you for this

Beautiful and inspiring. And now I want glass knitting needles.

I absolutely love this essay, thanks so much for writing and sharing it! I’m sending it to a dear fellow knitter-witch now ⬛

You can order yardage of the tartan or a scarf made of it. I ordered mine a couple of months ago. They are in the (second, I believe) weaving of it. So good of you to share this history and the news about the tartan, Ashleigh-ellan! Thank you.

Wow! Great essay; terrific food for thought. Thank you.

Very interesting. I never thought of textiles in this way.

Thank you for putting words to what I know intuitively. I appreciate the clarity with which you’ve crafted this articles, and I have bookmarked it to return to again in the future. And as it happens, I happen to own glass knitting needles, whose function has been expanded now. Cheers!

I love this piece! I started knitting a decade ago around the same time that I started reclaiming agency from my abusive parents. I was mid thirties, newly married with two kids and the birth of my youngest saw a deep creative surge pour out of me. I explored all crafts but knitting stuck. I started to remember that I had considered myself a witch as a child and I realised that yes, witchcraft is a thing and that I was indeed a witch! What is a witch? Essentially someone who believe in and worships the power of nature. I am proud to be a witch and proud to be a knitter, spinner, weaver and dyer. I’m even considering writing a PhD on the subject in the future. Thank you for this brilliant piece.

Very well said, all around. Great article!

Does anyone else think this reads like ChatGPT? Why is that?

Hi Concerned Witch,

I can assure you, this isn’t ChatGPT. As chatGPT is trained on a selection of large content, and as it proliferates the internet and our lives, it creates a kind of self-feeding circle of tone and style – meaning everything is at risk of sounding ChatGPTd eventually!

If you could see my absolute tangle and mess of notes that I write for each article, I’m sure you’d see the purely human elements here, even though many of them had to be polished off to create this finished article.

Thanks for your feedback though, and I hope you enjoyed the piece regardless.